Wildfires, vehicle emissions, petroleum by-products, and even cooking can conjure images of climate change. Each category also produces polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs, which are products of incomplete combustion. This group of hundreds of chemical species is toxic to human health, and as the world warms, more extreme weather will further exacerbate their presence in the atmosphere, said Natalie Johnson, an environmental toxicologist at Texas A&M University. Monitoring human exposure to these air pollutants, she said, is a public health issue.

In a new study published in the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, Johnson and her colleagues used silicone wristbands—like the ones worn by people supporting various causes—to track pregnant women’s exposure to PAHs. Their study took place in McAllen, Texas, which has high rates of premature births and childhood asthma—adverse health outcomes associated with poor air quality.

Highway to Poor Health

Studies show that mothers exposed to high levels of air pollutants have infants with an increased risk of developing respiratory infections, said Johnson. Moreover, if mothers live closer to sources of vehicle-related air pollution—like freeways—their children are more likely to develop asthma.

Three pathways transport PAHs into the human body, said Johnson. We can absorb them through our skin or ingest them by consuming charred foods. The third pathway is inhalation. This is a key pathway because our bloodstream can deliver PAHs throughout the body, she said. In pregnant women, the sanguineous superhighway can carry PAHs to the placenta. In this way, said Johnson, “[PAHs] can have some direct effects on the developing fetus.”

One problem PAHs can pose for people is cancer. By themselves, PAHs are typically not carcinogenic, but the pathways through which they can morph into cancer-causing molecules are known, said Pierre Herckes, an atmospheric scientist at Arizona State University who was not involved in the Texas study. Less well understood are the exact mechanisms through which PAHs might cause premature births and other adverse health outcomes in infants and children, he said.

Our bodies’ metabolisms can manage PAHs by converting them to free radicals, which are unstable, oxygen-bearing molecules that desperately want to react with anything that can give them electrons, said Johnson. Our bodies’ antioxidant systems can limit the impact of free radicals, she said. But when the scale tips toward more free radicals—more oxidants versus antioxidants—the antioxidant systems can become overwhelmed. The accumulation of free radicals can adversely affect growth and development in utero, she said, because “oxidative stress is tightly linked with inflammation.”

Too little inflammation leaves the body prone to viruses and bacteria, whereas too much results in the body overreacting to seemingly benign invaders, like dust. “Early in infancy, the prenatal exposures to these pollutants may cause immune suppression, and you may get inability to respond to important viruses like RSV,” said Johnson. The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) can be deadly for premature and young infants. Later in life, the same children exposed to these pollutants at an early age tend to have too much inflammation, triggering asthma attacks or allergic reactions, she said. Exposures at the earliest developmental stages—in the womb or during infancy—may increase the possibility of lung disease.

Silicone Sampling

One of Johnson’s graduate students, Jairus Pulczinski, mentioned to Johnson that other researchers have demonstrated the ability of silicone wristbands to passively sample pollutants. He suggested using them in an ongoing study of pregnant women in McAllen, which has poor air quality resulting from phenomena like Saharan sands blowing through the region and PAH-laden air wafting by from seasonal burning in Mexico.

Wristbands can qualitatively assess air pollution, said Johnson. “They’ve been really useful so far to say, ‘Yes or no, is there exposure?’”

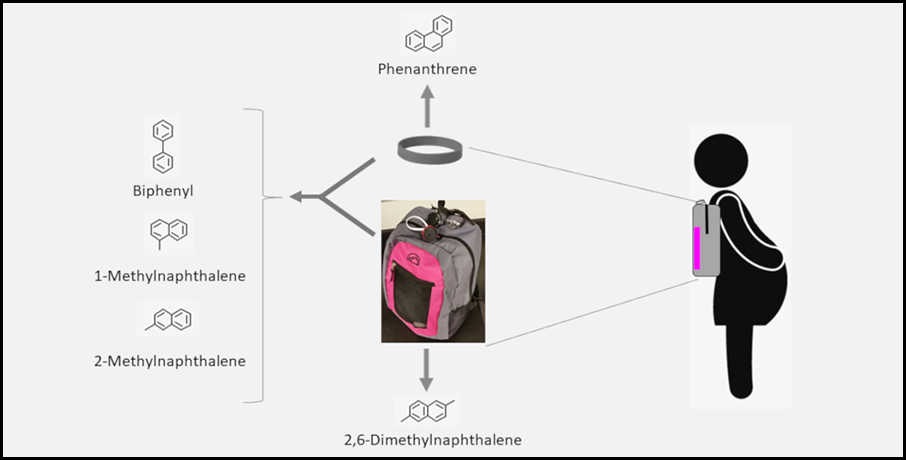

However, Johnson and her colleagues were more interested in air quality in this case. “In our study, we actually placed [wristbands] on small backpacks because we were also sending out active air monitors.” Within the backpacks, two tubes actively sampled the air. One tube sampled heavier, particulate PAHs, whereas the second tube sampled lighter, volatile PAHs. Seventeen expectant mothers carried the wristband-tagged backpacks for 24 hours, sampling the ambient atmosphere. The wristband results compared well with the volatile PAH sampling tube.

Health care providers could use information provided by the backpack sampler to help identify whether the person, for example, lives with a smoker or has an open fireplace—both PAH sources, said Herckes.

The data might also provide important clues about the geography of health care. “More studies show that exposure is different by socioeconomic situation,” Herckes said. The “bad” part of town might be closer to the highway or near industries that produce more air pollutants, and quantifying these deleterious effects could play a role in environmental justice, he explained.

Johnson and her colleagues provided guidance for limiting PAH exposure to the expectant mothers in McAllen who were part of the study. Good air filtration in the home is paramount, and monitoring the air quality index also helps.

Wristband research is now focusing on the quantitative side: How much air pollution has someone been exposed to? If the amount of exposure is known, said Johnson, scientists can start detangling just how much exposure is detrimental to mother or child. In the future, she said, they plan to explore whether air quality regulations are stringent enough to ensure safe pregnancies. This, she said, could inform future policy. “Doing anything we can to mitigate these environmental exposures could have a potentially big impact on public health outcomes.”

—Alka Tripathy-Lang (@DrAlkaTrip), Science Writer